Home > Blogs & Events > Blogs

June 3, 2020

Most people frown upon the idea of talking to machines, yet they are already encountering them in everyday conversations. For example, when you call a bank or utility company, you probably start the conversation with a bot that triages the request and escalates the conversation to a human call agent when it reaches the limits of its capabilities. There is no longer a need for a human to tell you your credit card balance. Likewise, there is no need for a human interpreter if a nurse checks on the temperature of a patient or if an airline attendant is helping you process a basic flight rebooking. This is where machine interpreting comes into play.

Machine interpreting (MI), often referred to as spoken translation, is the stepchild of machine translation applied to spoken content. While we include it as an interpreting modality, the intent is not to pit it against professional human interpreters but rather to simply explain its usage in contrast to traditional interpreting modes.

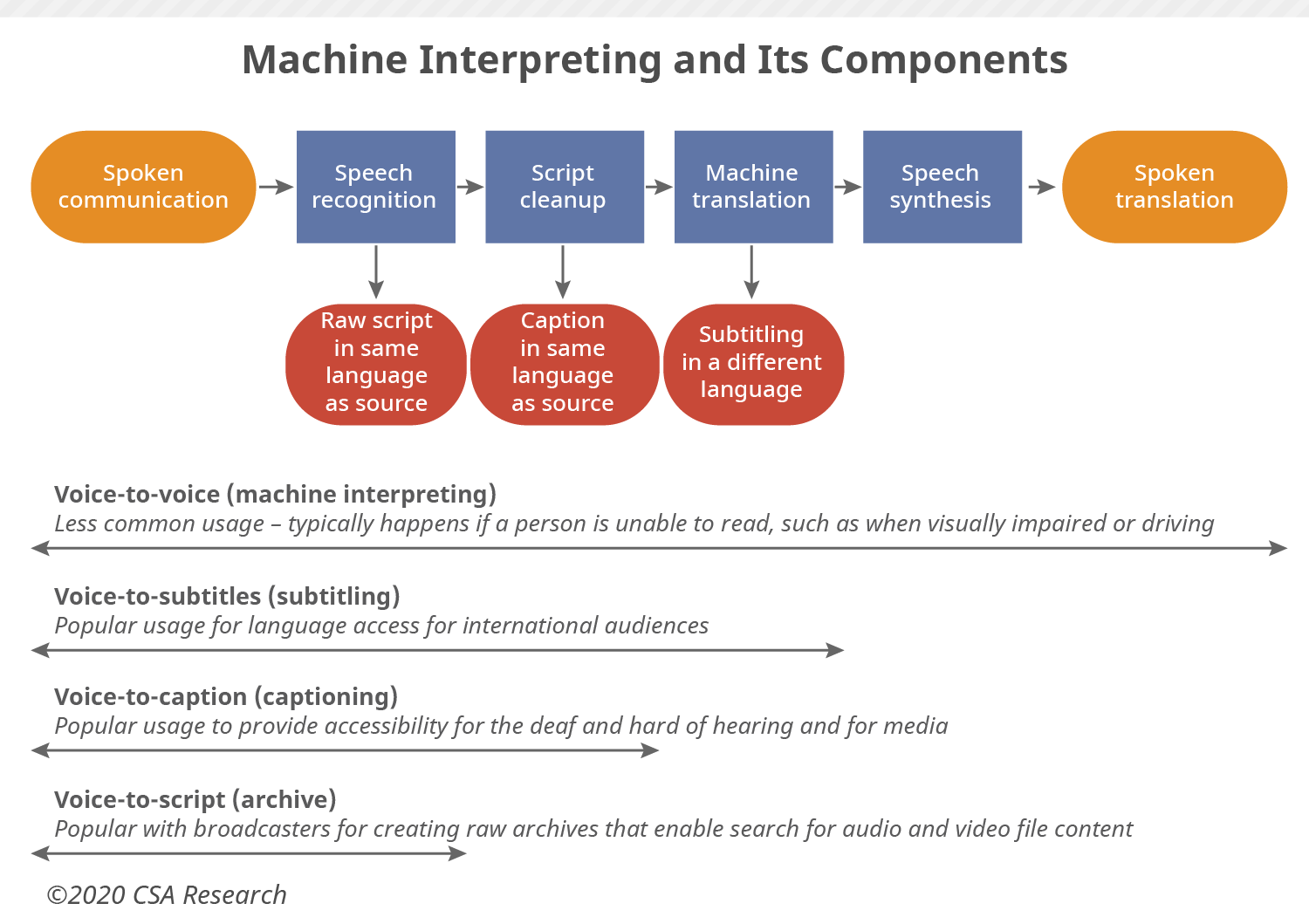

MI is the output resulting from an amalgam of four technologies: 1) speech recognition to convert the speech to text; 2) transcript cleanup and normalization to make the text machine-ready; 3) machine translation to translate the text into the desired language; and 4) speech synthesis to voice the translation.

Although MI is a voice-to-voice communication method, the process produces by-products that end up more useful in the eyes of many clients. Voice-to-script enables speech to last longer than its utterance and be searchable for future use. Voice-to-caption provides increased accessibility for the deaf and hard of hearing. And voice-to-subtitle is the key to language access – whether for recorded or live events. The full speech-to-speech roundtrip tends to be more limited to blind or visually impaired users or those otherwise occupied and unable to read (for example, people driving cars or operating machinery).

The market for machine interpreting remains very small. However, we’re seeing an uptick in terms of user comfort with and acceptance of MI technology, thanks in great part to the advances made with speech recognition and neural machine translation. In a survey of 40 enterprises in the second half of April, we found that 15% of them already use MI and 5% plan to do so. In addition, technology providers are reporting an uptick in interest from a broad range of client types.

Machine interpreting remains a sci-fi concept for most, but COVID-19 presents a noteworthy opportunity for the technology. While it may not gain as much traction as remote interpreting solutions that rely on professional human interpreters, it is catching the eye of organizations with limited budgets or that are thinking outside the box to solve the complexities of dealing with the pandemic.

COVID-19 may turn out to be a game changer for machine interpreting, but more so in the long-term as users may start to build some tolerance for the shortcomings of MI interpreting, especially in cases where the alternative is no access to language support.

MI has long been in the public eye, thanks to Star Trek and other science fiction franchises, but it is only now that it is becoming a mature and usable technology that responds to real-world needs. Its usability is rapidly improving and it will enable organizations and individuals to extend language support into environments where they would previously have left much of their audience unable to interact and communicate.

Subscribe to our newsletter for updates on the latest research, industry trends, and upcoming events.

SubscribeOur consulting team helps you apply CSA Research insights to your organization’s

specific challenges, from growth strategy to operational excellence.